As we move towards spring and the first potato seed treatments get underway, the inevitable questions arise: should we treat, or can we trim costs after a year of low crop prices? It’s understandable to hunt for savings, but there’s a critical disease we must keep front of mind, Rhizoctonia, because the decisions we make at planting can shape both yield and marketability at harvest.

Rhizoctonia: a one‑shot window to protect yield and value

Rhizoctonia doesn’t just reduce yield; it also lowers saleable value by causing black scurf on tuber skins. There is effectively one opportunity to tackle black scurf: on the seed tubers and, for a belt‑and‑braces approach, followed by an in‑furrow treatment. By the time the crop emerges, the window to control the causal pathogen on developing daughter tubers has passed. After a season’s worth of careful blight programmes, weed control, irrigation, fertiliser, and staff time, it’s a huge shame to arrive at harvest and find variable tuber size with skin discolouration from black scurf that knocks produce out of premium grades.

Low vs high input: what are we really optimising?

Debates about low‑input and high‑input systems typically fixate on spend. The real question is: what conditions are we optimising for, and how do returns actually behave across different seasons?

- High‑potential seasons (ample rainfall, warm temperatures, good sunlight) are often high disease‑pressure seasons. Where programmes are robust, disease is generally better controlled, allowing the crop to capitalise on the season’s biological potential and convert it into yield and quality.

- Low‑potential seasons (dry, low rainfall) usually carry lower disease pressure. In those seasons, the benefit of a leaner programme is the spend you didn’t make; additional crop protection often generates smaller biological responses because canopies are smaller and disease expression is limited.

This leads to a crucial insight from farm economics and risk management: state‑contingent payoffs and asymmetrical gains.

The asymmetry that tilts the maths

Crop protection investments such as fungicides, seed treatments, adjuvants, and biostimulants tend to pay non‑linearly with disease pressure, canopy size, and sunlight use efficiency.

- In a good year (ample leaf area + real disease pressure + decent tuber price), the marginal kg/ha gained per £ can be large. A well‑protected, vigorous canopy intercepts more light and fills more tubers into the target size bands.

- In a drought year (small canopies, limited infection), the incremental yield from extra protection is small; your loss is mostly the extra spend.

That asymmetry is the heart of the concept. A low‑input system only gains the saving in a poor year, but risks losing far more in the good years when biology would otherwise reward you. In potatoes, quality and size distribution amplify this effect; lifting the marketable proportion and improving skin finish can swing gross margins decisively. Flutolanil‑based seed treatments help here by protecting against Rhizoctonia solani, supporting more even emergence, stolon health and skin quality factors that all feed into saleable yield.

Putting numbers on it

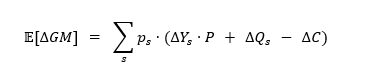

We can formalise the decision as an expected gross margin problem for any field and programme:

Effectively where the total growth margin for a season is a product of the likeliness that the value of output (including quality premiums) minus the cost of inputs is greater than zero, meaning the grower enjoys a positive benefit.

Where:

-

s indexes the seasonal state (e.g., dry/low disease; average; high disease & high potential)

-

pₛ is the probability of state

-

ΔYₛ is yield uplift (t/ha) in state

-

P is output price (£/t)

-

ΔQₛ is the quality/grade value change (£/ha) from better skin finish and size profile

-

ΔC is the additional input cost (£/ha)

The concept holds when E[ΔGM] > 0. In practice, that means a programme is justified if the probability‑weighted gains in yield and quality during high‑potential, high‑pressure seasons more than cover the added cost in low‑potential seasons – which, in almost all cases, they will.

Practical implications for potato programmes

- Prioritise one‑way windows

Interventions with a single opportunity to act (like seed and in‑furrow treatments against Rhizoctonia) deserve high priority because their upside in good seasons can’t be recaptured later.

- Target biological leverage

Spend where biology gives you multipliers by protecting early canopy development, ensuring even emergence, and maximising deposition/coverage in dense canopies.

- Account for quality, not just tonnes

In potatoes, marketability (size bands, finish, skin health) often moves the margin needle more than headline yield alone.

- Use adaptive layers

Keep a base programme that protects establishment and early canopy, then layer additional protection when models and field inspections indicate rising blight or soil‑borne disease risk.

The takeaway

In tight markets it’s tempting to trim crop protection budgets. But when you consider how returns arrive across different seasonal states, the economics often favour a well‑designed, high‑leverage programme, especially for one‑shot decisions like Rhizoctonia control. Protecting establishment and quality doesn’t just avoid losses in bad years; it unlocks the bigger gains that only materialise in good years.

In short: don’t let a low‑input mindset in February cost you your high‑output opportunity in September.